Introduction

As you may know from the popular histories,

the Romans left Britain at 'ten past four on a wet Tuesday afternoon',

and those unlucky enough to be left behind were forcibly supplanted

by a wholesale invasion of Angles, Saxons and Jutes! Yet, does this

widely accepted version of events make any real sense? OK, before

I attempt to explain my ‘hypothesis’ further, please disregard

the references to the time and weather as it should be fairly obvious

that they were complete fabrications! That said, when watching popular

television documentaries and listening to the bold statements of

‘subject matter experts’ (self-styled or otherwise), I

do sometimes wonder just how long it would take for such 'facts'

to gain their own credibility with the general public if repeated

often enough? And that got me thinking - just how sure are we of

the assertion that Germanic invaders ousted and replaced the entire

population, social structure, economy and language of Romano-Britain

post AD 500? To be fair, the popular invasion theory has been largely

supplanted by theories of mass migration across Europe in 5th and

6th centuries AD. Yet I cannot help feeling even this explanation

is still woefully inaccurate and increasingly unsupportable. Especially

as the traditionally accepted historical accounts, Gildas and Bede

for example, are re-evaluated in the light of modern scientific

techniques in archaeology, linguistics, and even genetics.

|

Changing Views.

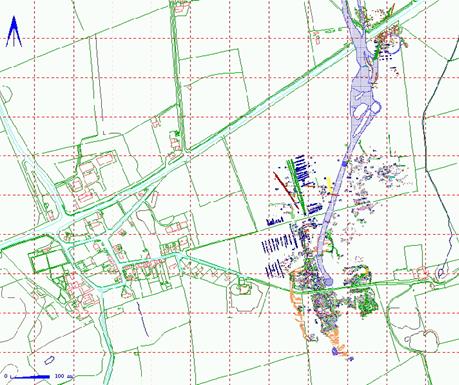

Improved archaeological techniques have revealed a continuity

of occupation at various ancient sites across the UK, even though

finds still tend to be catalogued, albeit largely for convenience,

as ‘Bronze Age’, ‘Iron Age’, ‘Roman’

or ‘Anglo-Saxon’. A superb example may be derived from

Dominic Powesland’s extensive geophysical surveys and subsequent

excavations at West Heslerton in the East Riding of Yorkshire.

Over the last two decades, the archaeology team’s investigation

has produced an extraordinary account of continuous occupation

from the Bronze Age into the 5th/6th century AD. Significantly,

there is little - indeed no - evidence of an ‘Anglo-Saxon

invasion’.

Foremost amongst the proponents of a rethink is

Dr. Francis Pryor, who has openly challenged a historical orthodoxy

that has held sway since Bede’s 8th century Historia Brittonum

(History of the Britons). In his book ‘Britain AD’,

for example, Dr. Pryor argues that a flourishing indigenous culture

endured through the Roman occupation of Britain and the so-called

‘Dark Ages’. Drawing on his archaeological expertise,

Pryor asserts that the alleged Anglo-Saxon invasion after the

fall of Roman Britain never happened in the way we think. So what

did happen? Can the study of genetics, for example, reveal the

‘truth’, or at least enhance the contrary evidence against

the persistent invasion theory.

Who are the Britons?

Despite their obvious proximity, Britain and Ireland are so thoroughly

divided in their histories that there is actually no single word

to refer to the inhabitants of both islands. Historians teach

that they are mostly descended from different peoples: the Irish

from the Celts, and the English from the Anglo-Saxons who invaded

from northern Europe and drove the Celts to the country's western

and northern fringes. Yet, genetic studies of DNA throughout the

British Isles are edging toward a different conclusion. Many geneticists

are struck by the overall genetic similarities, leading some to

claim that both Britain and Ireland have been inhabited for thousands

of years by a single people that have remained in the majority,

with only minor additions from later invaders like Celts, Romans,

Angles, Saxons, Vikings and Normans.

The implication that the English, Irish, Scottish

and Welsh have a great deal in common with each other, at least

from the geneticist's point of view, is unlikely to please many

desperate to maintain the distinction. The genetic evidence is

still under development, however, and because only very rough

dates can be derived from it, it remains difficult to convincingly

weave evidence from DNA, archaeology, history and linguistics

into a coherent picture of British and Irish origins.

Arguments from Genetics.

That has not stopped the attempt. Stephen

Oppenheimer, a medical geneticist at the University of Oxford,

simply believes the historians' account is wrong in almost every

detail. In Dr. Oppenheimer's reconstruction of events, the principal

ancestors of today's British and Irish populations arrived from

Spain about 16,000 years ago, speaking a language related to Basque.

On the basis of the available genetic data, Dr. Oppenheimer believes

no single group of invaders is responsible for more than 5% of

the current gene pool. Estimates by the archaeologist Dr. Heinrich

Haerke suggest that the Anglo-Saxon invasions, beginning in the

4th century AD, added about 250,000 people to a British population

of one to two million. Dr. Oppenheimer notes this figure is larger

than his but considerably less than the substantial replacement

of the British population assumed by others. As a comparison,

Dr. Haerke has calculated that the Norman invasion of AD 1066

introduced not many more than 10,000 people.

Importantly, Dr. Oppenheimer's population history

of the British Isles does not rely solely on genetic data but includes

the dating of language changes by methods developed by geneticists.

Currently the techniques are not generally accepted by historical

linguists, who have already developed but largely rejected a dating

method known as glottochronology. Geneticists, having recently plunged

into the field, argue that linguists have been too pessimistic and

that advanced statistical methods developed for dating genes can

be applied to languages. For example, the work by Dr. Peter Forster,

a geneticist at Anglia Ruskin University, argues that Celtic is

a much more ancient language than previously supposed, and that

Celtic speakers could have brought knowledge of agriculture to Ireland,

where it first appeared. Accordingly, Dr. Oppenheimer agrees with

Dr. Forster's argument, based on a statistical analysis of vocabulary,

that English is an ancient, fourth branch of the Germanic language

tree, and - this is the key - was spoken in England before the Roman

invasion. |

|

The Mother

Tongue?

Tradition has it that ‘English’ developed in England,

from the language of the Angles and Saxons, about 1,500 years ago.

Yet Dr. Forster argues that the Angles and the Saxons were both

really Germanic peoples, originating from the Scandinavian region

(Vikings?), who began raiding Britannia ahead of the accepted historical

schedule. They did not bring their language to England because an

embryonic ‘English’, in his view, was already spoken there,

probably introduced before the arrival of the Romans by tribes such

as the Belgae, who were resident on both sides of the Channel. The

Belgae may have introduced some socially transforming technique,

such as iron-working, which may have led to their language supplanting

that of the indigenous inhabitants. Dr. Forster stresses, however,

that he has not yet identified any specific innovation from the

archaeological record that would wholeheartedly support this theory.

The point is that the inhabitants of Britain were not isolated from

Europe but shared a cultural heritage, technological innovation,

trade and, it seems reasonable to assume, a common language - for

trading if nothing else.

A Common Linguistic Origin.

Germanic is usually assumed to have split into three branches:

West Germanic, which includes German and Dutch; East Germanic,

the language of the Goths and Vandals; and North Germanic, consisting

of the Scandinavian languages. Dr. Forster's analysis shows English

is not an off-shoot of West Germanic, as usually understood, but

is a branch independent of the other three, implying a greater

antiquity. Historians have traditionally assumed that ‘Celtic’

was spoken throughout Britain by the time the Romans arrived.

But Dr. Forster estimates that Germanic split into its four branches

some 2,000 to 6,000 years ago. If correct, this increases the

likelihood that the ‘Celtic’ associated with Britain

may have been misidentified and was instead the fourth branch

of the Germanic language tree. As argued by Dr. Oppenheimer, the

apparent absence of ‘Celtic’ place names in England

(words for places are particularly durable) supports the theory.

From one who is uncomfortable with the hackneyed Anglo-Saxon history

of Britain, the continuity of a Germanic based language seems

to make more sense. It suggests that, during the Roman period

at least, Latin was probably a convenient veneer - the lingua

franca essential for commerce and, importantly, the government

of diverse peoples (with a multitude of languages, dialects, etc,)

across the Empire. With the waning of Roman influence and the

breakdown of trade links across a fragmenting Empire, the persistent

underlying Germanic language of the Britons simply supplanted

Latin. Moreover, it seems sensible that the migration of other

Germanic speaking peoples into western Europe would have encouraged,

if not demanded, a resurgence of a common language for trade and

interracial relations.

An Argument Won?

Archaeology, linguistics and, more recently, genetics are providing

evidence of a cultural continuity in Britain incompatible with

theories of invasion or widespread population displacement. Increasingly

the British appear to have a Germanic heritage independent of

the Anglo-Saxon history created by medieval writers who sought

for political or religious reasons to present a common origin.

So, if the people of the British Isles have a shared genetic heritage,

with their differences consisting only of a regional flavouring

of ‘Celtic’ in the West and of northern European in

the East, might that draw them together? There is, however, little

prospect that the geneticists’ findings will reduce cultural

and political differences amongst Britons. Genes, as Dr. Oppenheimer

says: “have no bearing on cultural history...There is no

significant genetic difference between the people of Northern

Ireland, yet they have been fighting with each other for 400 years”.

A quote by Dr. Bryan Sykes, another Oxford geneticist is very

telling: “[The Celtic cultural myth] is very entrenched and

has a lot to do with the Scottish, Welsh and Irish identity; their

main identifying feature is that they are not English." Importantly,

Sykes agrees with Dr. Oppenheimer that the ancestors of "by

far the majority of people" were present in the British Isles

before the Roman conquest of AD 43. The emerging evidence and

new theories reveal that the Saxons, Vikings and Normans had a

minor effect, and much less than some of the medieval historical

texts would indicate. Anglo-Saxon invasion...what invasion?

|