|

One of the interesting things about our hobby,

but one which can also be the most frustrating, is the way our

knowledge of the Roman army and its equipment is continually being

expanded by new discoveries. Sometimes this allows us to introduce

new items which allow for a more interesting interpretation or

sometimes a more practical approach to things. However, all too

often it tells us that we have we have fallen behind the current

state of the evidence and need to make improvements to kit in

the light of an enhanced level of knowledge. Regrettably this

can end up costing us money we would sometimes rather not spend

and this is a common problem experienced by most re-enactment

groups of most periods.

In the light of this, it is an unfortunate

fact that many of our sword scabbards now fall into this category

and need to be upgraded or replaced in the light of what we now

know about the evidence they are based on. This includes my own

scabbard.

|

|

The scabbards I am talking

about here are the ones which feature locket plates decorated with

two large embossed 'X' shapes. These are based on Micheal Simkins

interpretation of pictures of a fragmentary locket plate from Long

Windsor (figure 1), now in the

Ashmolean Museum. In the mid 1970s, when Simkins proposed the pattern

of locket plate commonly seen in the RMRS, far fewer Pompeii type

scabbard parts were known than are know to us today. At the time

the only known Pompeii type locket plates he knew of were the four

from Pompeii itself and one other from Leiden in Holland. The Long

Windsor find consisted of a Pompeii type sword and its fragmentary

scabbard. Although the remains of the locket plate measured less

than half the length of the Pompeii and Leiden examples, Simkins

made the quite reasonable assumption that the Long Windsor plate

would originally have been of the same dimensions as the other know

Pompeii type locket plates, with two decorative fields. His interpretation

of the piece was that it had originally had an 'X' shape embossed

into it (which had later corroded away) and given that the assumed

lower area of the plate was not present, he repeated the pattern

on the lower field of his reconstruction which he found on the surviving

portion. At the time his interpretation was sensible and reasonable

and seemed a good interpretation of the evidence. It became known

as the 'Simplified Simkins Pattern' locket.

So far so good then, until new evidence turned up to call Simkins'

interpretation of the Long Windsor plate into question. In 1996,

Martin White, of the Ermine Street Guard, published an article which

convincingly showed, based on a closely comparable locket plate

from Valkenburg in Holland (figure

2), that the Simkins' interpretation of the Long Windsor

plate had been wrong and that the plate had not been embossed but

had instead had the 'X' shape inscribed into it, along with a number

of small punched circular shapes. Another comparable locket plate

had been discovered some time before at Vindonissa in Switzerland

(figure 3) but was not widely known

at the time. |

Figure 1: The Long Windsor locket plate

Figure 1: The Long Windsor locket plate |

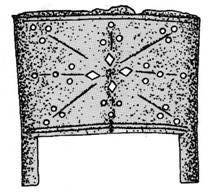

| Since then five more examples

have come to light and they now comprise a distinctive group of

a completely different type of locket plate to what had been known

before. These other examples are a plate still incorporated in a

scabbard from Porto Novo (figure

4), an unprovenanced plate currently in a museum in Budapest

(figure 5),

an unprovenanced find from somewhere in the Balkans, now in a private

collection (figure 6), a plate from

Lobith in Holland featuring an inscribed warrior in a chariot (figure

7) and a plate still incorporated in the remains of a scabbard

from Rajkova-Mogila, currently in the National Museum in

Sofia (figure 8). This last example

appears to be embossed and features a motif of the wolf and twins. |

Figure 5: The Budapest locket plate.

|

|

As will be seen from the pictures, these locket

plates are all much shorter that the other type of Pompeii scabbard

locket and all feature short legs which extend down to the point

where the scabbard would be crossed by the upper cross hanger

holding the upper suspension rings (as can still be seen on the

Porto Novo and Rajkova-Mogila examples), inscribed

horizontal lines at top and bottom and often feature gamma shaped

cutouts, further decorative cutouts, radiating inscribed lines,

small punched circles, figural designs and scalloped lower edges.

All of these plates appear to have featured a retaining band near

the top which passed around the rear of the scabbard.

It is worth pointing out at this point that

these lockets may come from a transitional type of scabbard. Although

the Long Windsor plate was associated with a Pompeii type chape,

the Porto Novo scabbard was closer to the dimensions of a Mainz

type scabbard but also featured the ‘palmette decoration

associated with Pompeii type sheaths.

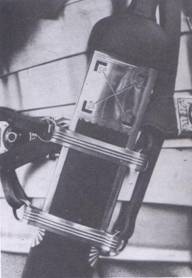

Figures 9 and 10 show reconstructions of the updated interpretation

of the Long Windsor plate and the Vindonissa plate.

Acknowledgements

Figure 1 N. Griffiths

Figures 2-8 C. Miks

Figures 9-10 Ermine Street Guard

Sources

Martin White, 'Pompeii Scabbards' - Exercitus

1996

Christian Miks, Studien Zur Roemischen Schwertbewaffnung In Der

Kaiserzeit 2007

Epilogue

A good point that has often been made is

that at any one time the Roman army must have had around a quarter

of a million sets of equipment in service and with what we have

to study comprising less than one percent of this, it is often

unwise to get too prescriptive about how something was or was

not done. Therefore a certain amount of assumption will always

have to be used in addition to the strict evidence which has survived,

as long as it starts from the evidence and works outwards from

there.

This is generally a safe 'fall back' position.

However, in this case we have an instance of the evidence having

increased, which in turn has shown that the old interpretation

of one part of it had been seriously and verifiably flawed.

Therefore, regrettable as it may be, the time has

now come when we need to start phasing the Simkins pattern locket

out of the group. This should start with no further examples being

introduced, and then continue as individual members either replace

their scabbards with more accurate ones or have their scabbards

upgraded to fit better with the current state of the evidence,

hopefully with minimal cost being involved, until we reach a point

in perhaps two or three years' time when the old Simplified Simkins

pattern lockets are nothing more than a fond memory to be found

in old photos of the group. As long as all of the Simkins plates

are replaced with reproductions of designs known to be correct,

no similar upgrading of scabbards should be needed again for a

very long time (and hopefully never). For those who wished to

upgrade, rather than replace, their scabbards, replacement locket

plates could easily be produced and fitted.

Crispvs

|

Figure 9: The Long Windsor reconstruction.

Figure 10: The Vindonissa reconstruction. |