|

|

| |

The Manica in the Roman Army up

to 150 AD Caballo

(Paul Brown) 2007

|

| |

Roman legionary , Dacian Wars- with kind permission

from Jim Bowers

|

| |

1. Introduction

Recently, the Carlisle finds have led to old conclusions

about the manica being re-visited (e.g. “It was only used against

the Dacian falx-men”) and old finds being re-evaluated (the

Newstead finds). Manicae have been seen reconstructed by a number

of re-enactment groups- most notably in the Ermine Street Guard.

This article aims to pull together the many excellent

articles and book chapters on the manica in early Imperial Roman

times (0-150 AD) , and to give amateur historians and re-enactors

alike an easily referenced article on the manica - what it is, when

it was used, and some thoughts about how it could be re-constructed.

I would particularly like to thank for help, advice,

and permission to use photographs, drawings, and conclusions Dr.

Mike Bishop, Dan and Susanna Shadrake, Adrian Wink, and Jim Bowers.

Any errors and minor to catastrophic failures of judgement and knowledge

are entirely down to me!

I will aim to give a short history of the manica,

look at the Roman evidence - written, sculptural, mosaic, and (most

importantly) actual finds. I will then go on to describe possible

re-constructions, experiences of modern users, and then draw some

conclusions.

What is a manica?

I will define a manica is a segmented arm protector

made of iron or cupric alloy- leaving the textile and leather arm

protectors to other , more knowledgable individuals.

2. History

The manica has a long history, with Xenophon

describing cavalry of 4th/5th century BC equipped with an articulated

armguard, a ‘Cheira’ on the left arm in place of a shield.

In Pergamon, pieces of an iron armguard were

found, and armguards are also depicted in the sculpture at the Temple

of Athena at Pergamon.

At Ai Knaum, another segmented armguard was found

in the Hellenistic arsenal dated to 150 BC. This had a large upper

plate and about 35 over-lapping curved plates, which appear to “under-lap”

downwards from the hand/wrist plates- that is, with each plate being

under the next as it goes up the arm. This would protect and deflect

a sword or spear thrust. The opposite way (plates over-lapping downwards)

would deflect the enemy’s spear point into the gap between

the plates towards the unprotected arm – which, on balance,

is probably not a good idea

3. Roman evidence

a. 0-50 AD Gladiators.

Gladiators demonstrate a wide variety

of armguards- in metal, leather, and padding.

|

| |

|

| |

However, a key development came

with the crupellarius- a heavily armed gladiator of Gaulish origin.

Tacitus describes their use is fighting against legionaries in the

revolt of Florus and Sacrovir of AD21:-

"There was also a party of slaves training

to be gladiators. Completely encased in iron in the national fashion,

these crupellarii, as they were called, were too clumsy for offensive

purposes but impregnable in defence…the infantry made a frontal

attack. The Gallic flanks were driven in. The iron-clad contingent

caused some delay as their casing resisted javelins and swords.

However, the Romans used axes and mattocks and struck at their plating

and its wearers like men demolishing a wall. Others knocked down

the immobile gladiators with poles and pitchforks , and, lacking

the power to rise, they were left for dead." Tacitus, Annales,

III 43

As it happens, a bronze figure was found at

Versigny, France that matches this description, and is reproduced

below (with kind permission on Mike Bishop and Susanna Shadrake)

|

| |

|

| |

As can be seen, this

segmentation covered both arms, body, and legs.

A rather wonderful re-enactment of this Ned Kelly of the Roman world

has been made by Familia Gladiatoria of Hungary- and it is a sight

that must have impressed watching soldiers.

|

| |

Crupellarius reconstruction - with permission

of Familia Gladiatoria of Hungary

Crupellarius reconstruction - with permission

of Familia Gladiatoria of Hungary |

| |

Further evidence- this time placing

the metal manica firmly in the Roman army, comes from the tombstones

of Sextus Valerus Severus and Gaius Annius Salutus, both from Mainz

and legionaries of Legio XXII Primigenia, who were based in Mainz

between AD 43-70. Their tombstones show manicae as part of the decorative

border of weaponry surrounding the text of the tombstone. Severus'

manica shows eleven plates and a hand shaped section of four plates

(though it would be unwise to rely on this sculptural reference as

opposed to the archaeological finds). However, this clearly places

the manica as being used- although rarely- by Roman legions on the

Rhine around AD 43-70.

b. Roman Exidence 50-150 AD

Sculptural evidence

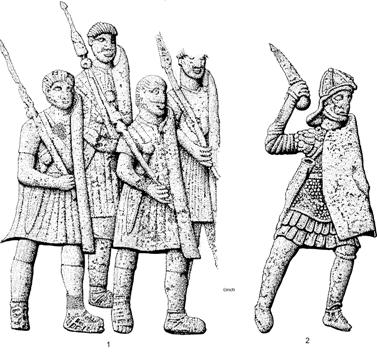

The most useful source is the Tropaeum Traiani metopes

at Adamklissi, constructed c. 107/8 and depicting Trajan’s

Dacian wars. Although the same campaign as shown on Trajan’s

Column, the equipment shown is very different. As a monument set

up closer to the front line and the actual soldiers - and less of

a “Head Office” official propaganda monument like Trajan’s

Column- Adamklissi is generally regarded as being more accurate

in its depiction of the troops.

Of the metopes showing troops in battle, virtually

all show legionaries wearing manicae on their sword or spear arm.

Those that do not show:-

-Auxilaries (metope XIV)

-Cavalry (metope 1)

One legionary, dressed in mail with a scutum (metope

XXIX) does not appear to wear a manica, though the stone is damaged.

Some others have suffered similar or worse damage, and it is not

possible to conclusively prove that manicae are depicted in these

pieces..

Troops marching or off-duty, standard bearers, cornicens,

attending senior officers, or holding captives do not wear manicae.

Legionaries are shown in mail or scale, but

not in lorica segmentata as on Trajan’s Column. Helmets with

cross-bracing and greaves are also depicted. Auxilaries are shown

in mail, with senior officers in lorica musculata

|

| |

Legionary with mail, manica and spear with Dacian

falxman

Legionary with mail, manica and spear with Dacian

falxman |

Legionary in scale, holding sword and Dacian

falxman

Legionary in scale, holding sword and Dacian

falxman |

| |

Legionary in mail, manica with sword and Dacian

falxman

Legionary in mail, manica with sword and Dacian

falxman |

Legionary in scale, manica with sword and two

Dacian falxmen

Legionary in scale, manica with sword and two

Dacian falxmen |

| |

(All pictures reproduced with kind permission

of Jack O'Keefe and Legio XX of Ireland.)

|

| |

Marching "offduty" soldiers, compared

with soldier in combat

Marching "offduty" soldiers, compared

with soldier in combat

(With kind permission from Mike Bishop)

|

| |

It is understandable that the theory

grew up that the manica was brought in to combat the fearsome Dacian

falx, whose wielders were later to guard the Emperor himself (see

column of Marcus Aurelius and coinage). However, archaeological finds

elsewhere invalidate this theory.

Archaeological evidence

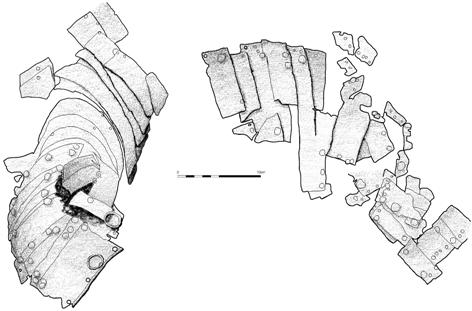

A number of finds have been made- or subsequently

recognised as manicae. The first was from the Waffenmagazin at Carnuntum,

followed by the copper alloy curved plates from Newstead, which

also provided pieces belonging to an iron manica. Both came from

the well in the headquarters building that also conserved the Newstead

lorica segmentata. These were (incorrectly) described by Robinson

as thigh guards, and the finds are probably not complete, with more

plates/ lames being in the original.

|

| |

Newstead Manica (copper alloy) , National Museums

of Scotland

Newstead Manica (copper alloy) , National Museums

of Scotland |

| |

Further plates have

now been identified from Richborough, Corbridge, Eining, Leon, and

possibly complete manicae have been found at Carlisle and at Ulpia

Traiana Sarmizegetusa in Dacia/ Romania .

The finds of manicae therefore stretch across the

Roman Empires- and cannot be simply a defence against falx-men.

The Carlisle finds, from a Hadrianic context

are the most important (though I have been unable to obtain photographs

and details of the Romanian find). It appears to be one complete

iron manica. In addition, two halves of two other iron manicae were

found. I understand that two further manicae were found, but these

are yet to be examined and published.

|

| |

Carlisle Manica (with kind permission from Mike

Bishop)

Carlisle Manica (with kind permission from Mike

Bishop) |

|

|

X rays of the manica when found also show

convincingly that the manica plates under-lapped from the wrist- to

provide better defence against a thrust.

One has surviving copper-alloy ring fittings- another a hook similar

to lorica segmentata fastenings.

|

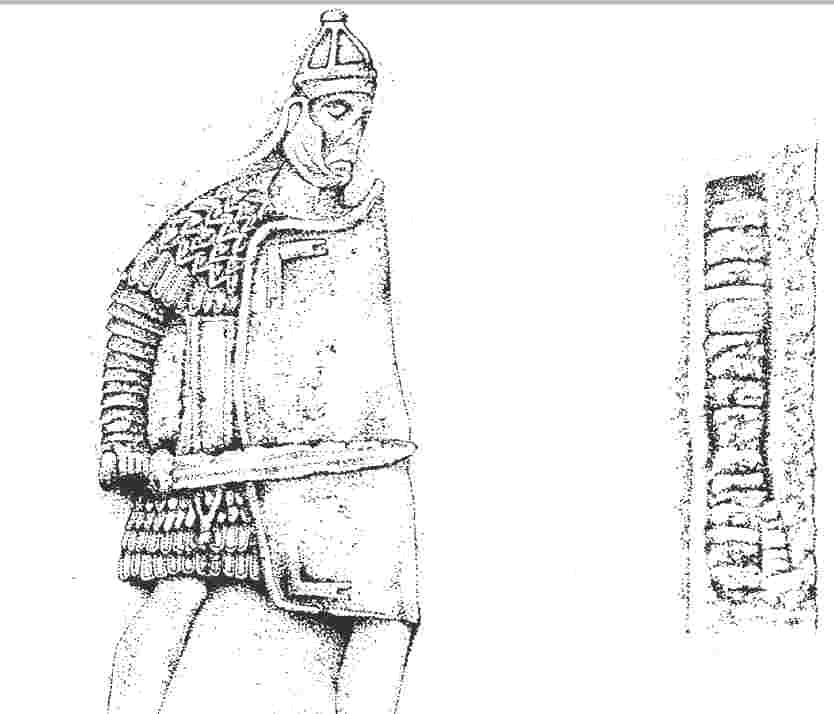

| Right. A legionary infantryman from

the Adamklissi Monument, showing a "manica lamminata"

with body defences of 'pteruges' and a corset of scale. |

|

Left. The crude representation of a

"manica laminata" from the border of the grave stele of

the legionay infantryman Sextus Varus Severus. The arm guard appears

to show complete coverage of the fingers and thumb of its owner. |

| |

|

| |

c. Roman Evidence Post 150 AD

After 150 AD (though not the main aim of this article), further

evidence exists for Gladiator manicae, with both mosaics and references

to ‘Manicarii’ at the gladiator training schools during

the reign of Commodus.

The 2nd/ 3rd century relief at Alba Julia shows a legionary wearing

a segmentata (of unique design) and a manica

Alba

Julia relief (by kind permission of Mike Bishop)

In Dura Europos, the famous “clibanarii” graffito appears

to depict manicae, which are also shown in medieval copies of the

(much) later ‘Notitia Dignitum’.

Finally, Ammianus describes Roman cavalry on parade in 350 AD as

“Laminarum circuli tenues apti corporis flexibus ambiebant

per omnia membra diducti.” (Thin circles of iron plates,

fitted to the curves of their bodies, completely covered their limbs).

4. Re-creating the manica

Based on the work of Mike Bishop, the armguards had about 35 iron/

steel or copper alloy plates below the main upper plate, articulated

on internal leathers fastened by copper-alloy rivets. The upper

plate (based on Newstead) is 25.8 cm long and 9 cm wide, with a

turned upper edge and holes for the attachment of a lining and straps,

tapering down to the smallest plate of 12cm long. The lower plates

were 2.7 cm wide.

Comparing with the Carlisle manica, the main plates varied between

25 and 30 mm wide, again shortening as they progressed down the

arm.

At the wrist, the Eining and Leon examples were riveted together

and not articulated.

Some kind of padding also existed, and Van Groller noted remains

of linen and leather. The Newstead manica also had fragments of

leather surviving when it was first found.

Susanna Shadrake and Britannia have also noted the tendency of

the manica to rotate around the arm in combat- also noted by some

other groups who have used these in combat. This can be counter-balanced

by a disc being worn around the pectoral area- as seen in the mosaic

below (also on the cover of her highly recommended book "The

World of the Gladiator".) No unequivocal evidence has so far

been found of such discs in a military context, but some such device

seems likely.

|

| |

4th Century Villa Borghese mosaic, reproduced

with kind permission of Susanna Shadrake

4th Century Villa Borghese mosaic, reproduced

with kind permission of Susanna Shadrake |

| |

Britannia's reconstructions show

that an unsecured metal manica needs a strap, like a baldric, passing

under the shield arm, if it is not to slip down under its own weight.

A padded manica made of fabric, in contrast, stays up held by the

thonging that ties it to the arm.

Finally, the manica is primarily worn on the

upside of the arm, and not over the elbow. This is because this

would be the most exposed part of the arm when using a sword . This

is supported by the design as a manica going over the elbow would

need a couter plate to allow the manica to expand over the joint.

No such plate has been found.

|

| |

"Correct" method of manica position:

Picture by kind permission of Jim Bowers

"Correct" method of manica position:

Picture by kind permission of Jim Bowers |

| |

This seems to contradict some sculptural

representations- but is supported by the actual finds. Of course,

the longer the plate, the more it could encircle the arm and give

more protection.

Overall, in reconstructing the manica, the following

components are likely

-Shoulder plate - 1

-Lames - c. 35

-Leathering copper-alloy rivets -90-120

-Internal leathers - 3-4

-Padded fabric and leather lining - 1

|

|

|

|

|

|

Replica manica based on the Carlisle finds,

reproduced with kind permission of Susanna Shadrake and

Michael Hardy

|

|

|

Manica on the Column of Arcadius (AD 402)

This corroborates the Notitia Dignitam in confirming manica

use in the late fourth / early fifth century.

|

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the manica- having had a long history

before- came into the Roman army between AD 21 and 70, with widespread

use throughout the Empire. At the moment, only legionary use is

attested but of course “absence of evidence is not evidence

of absence”. It appears to be a combat item of equipment, and

not used day to day.

“Official sculpture” does not depict the

manica, which is only shown in sculpture from the “front line”

in Dacia and the Rhine. It is only possible to speculate why this

might be, but it might be thought that a gladiator-associated item

of kit should not be shown on a soldier and citizen of Rome? Gladiators,

despite their “footballer celebrity” status, were also

regarded as somewhat degraded- “solemnly handed over body and

soul to our masters” (Petronius, Satyricon 117) and Augustus

prohibiting young men of rank from becoming gladiators.

Finally, it is completely justified for re-enactment

groups depicting first century Rome to have members wearing a manica

if a potential combat situation is to be shown.

Key Bibliography

Lorica Segmentata, Volume 1- M.C. Bishop

The Armour of Imperial Rome- H.R.R Robinson

The World of the Gladiator- Susanna Shadrake

A Roman Frontier Post and its People- James Curle

Various members of the society have adopted

different means of attaching their manica.

To read articles relating to this click

here. Note the file is 1.6MB

|

|